New writers often ask me: does it get easier after the first book? And of course in some ways it does. Doing something difficult once gives you confidence and permission to do it again. But ask a novelist who’s published 22 books which was the hardest to write and I bet she’ll answer, ‘Number 23’.

Each book brings new challenges. Some are obvious: you can’t use the same plot twist twice, for example. Themes, now that I have a solid backlist, are emerging. I cannot, it seems, leave the 1990s alone, or make peace with the fact that I am no longer nineteen. In the zombie procession of dead and dying mothers shuffling through my books, I have written and rewritten my twin greatest fears: of not being able to mother my daughters: of losing my own mother. I’m aware of the thin line between familiarity and repetition.

Research is increasingly an issue. ‘Write about what you know’ gets old pretty quickly when you’re essentially a suburban mum. To challenge myself, as well as keep readers entertained, I need something – setting, backdrop, crime – to change every time.

I’m about to publish my sixth book, and deep into my seventh. Here’s what it has been like for me.

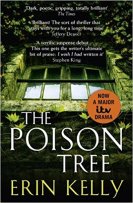

Book One: The Poison Tree

I wish I had known, when writing this novel, what a beautiful experience it was, but there you go; you can’t pop your cherry twice. I’d wanted to write fiction my whole life. By 2007, this ambition was beginning to coalesce; I’d done a couple of short courses and joined a writing group but still had no more than a handful of sketches to show. Then, in 2008, I got pregnant and the biological deadline galvanised me. I flipped my usual work routine: treating the novel as my day job, scratching a couple of hours’ journalism in the evening (and yes, the financial fallout was as you’d expect). But six months later, I had a book. It was only 60,000 words long, and it would change before being accepted, but it was a book.

At the time, I was the usual mess of doubt and worry that I was about to make my family homeless through what is essentially vanity. Now I look back and realise what a treat it was, what a joyous rush of instinct and naivety. A lifetime’s love of books, my own internal library, welled up and bubbled over onto my page. It was as smooth as laying an egg. There was almost no research involved. I remember agonising for weeks over a plot turn that now seems almost laughably simple.

This book was very good to me and I still love the characters and the story. I do twitch to go through it with a red pen. After years of disciplined journalism, the freedom to really write went to my head and it’s overwritten in places. The foreshadowing is pretty heavy-handed. And – since I appear to be in the confessional here – there are a handful of places where I rewrote scenes because my characters didn’t seem enough like people from a novel. I know now, of course, that the goal is the opposite.

Book Two: The Sick Rose

I wrote this book in a bubble. A two-book deal had given me relative financial security, validation and encouragement. Crucially, though, I still hadn’t been published. Never been reviewed; never woken up at 2am and fired up my laptop to check my Amazon ranking. Also I wasn’t on Twitter yet.

Like The Poison Tree, The Sick Rose – about a troubled older woman’s affair with a vulnerable 19-year-old – used a then-and-now structure but with an added layer of complexity as the to-and-fro had two narrators. It was a step up in terms of structure.

It’s set partly in a ruined Elizabethan castle, so for the first time I had to research. I read widely and obsessively about the massively sexy area of heritage gardens, specialising in Tudor parterres. Almost none of it ended up on the page, but my learning leaks between the lines.

Louisa and Paul, my narrators, were good to me. I want to deliver the best-written, most convincing suspense I can, and this inevitably means tension between what the plot needs and what the character wants. Most of my work is about finding the sweet spot where you can be true to both, and I hope I always get there in the end but some fight harder than others. Paul Seaforth, a geeky, oversensitive and horny 19-year-old from a rough estate in estuary Essex remains my favourite of my characters, not because he’s the most magnetic but because he served me so well. I never felt I was making anyone in The Sick Rose act out of character for the sake of the story.

Book Three: The Burning Air

This bloody, sodding book. I’ve never cried because of something I’ve written, but there was a moment, a year into this novel, when I burst into tears of frustration.

Before I started The Burning Air, my then American editor said she wanted to see the first third before making an offer on it. So I wrote 25,000 words of pure suspense. It was a story about an extended family gathering in their deserted country house for Bonfire Night. This first act finished with a baby being kidnapped, and the family realising that the night’s events had their roots in family secrets. I wrote it in real-time, 24-style, merrily littering it with clues and red herrings, with no idea how I was going to resolve it. I was Houdini closing the padlocks without an exit plan.

I wrote maybe 90,000 words of convoluted, melodramatic backstory before paring it down to a ‘mere’ 40,000 that bridged the link between a past slight and the present-day revenge. I sailed months past my deadline.

In the end, I pulled it off. Five years later, I still get emails about the twist that comes halfway through the book. Half congratulate me on sleight of hand. The rest complain that they thought one thing but it turned out to be quite another, thus spectacularly missing the point of suspense. More insightful readers ask me whether I the twist is needless showing off. The honest answer is: a bit. It’s gratuitous in that the plot still holds without it. Actually, the twist came almost by default. I left a certain detail blank to keep my options open, then realised I had an opportunity to have some fun with the reader.

Most importantly, The Burning Air was the book that taught me never to give up. Had I experienced this level of self-doubt with a first novel, I probably would have abandoned it. If I can rescue this, I can see anything through to the end. I vowed after writing it though that I would never write like this again, coming up with a great high-concept opening that was torture to execute. It is with a heavy heart that I refer to you my notes on Book Seven, below.

Book Four: The Ties That Bind

I wrote this book on the rebound from the claustrophobic, very domestic, very female nature of The Burning Air, and, if I’m honest, my actual life. The result was Luke, a gay male journalist investigating the unsolved murder of a gangster in 1960s Brighton. The Ties That Bind (its working title was Ransomed Soul, which I still prefer) opens with him tied up in a cellar: who put him there? His possessive ex, Jem, or Joss Grand, the ‘reformed’ career criminal whose past Luke’s been raking over? Influenced by Graham Greene and Jake Arnott, it’s the closest thing to pure crime fiction I have ever written: still not a procedural but an investigation, with evidence and a paper trail, long scenes of interrogation and confession. There are only two women in it. There are no flashbacks. It is the most straightforward of my original books and was the easiest to write.

It has made me wonder whether the easier a book was to write, the less readers love it. The sales figures were pretty… sobering. The lessons I learned from this book were about publishing rather than writing Ties is a good book and contains some of my most disciplined writing, but it’s subtly different to my backlist, harder to market as a crossover between women’s fiction and crime. I knew when I wrote it that I was dipping a toe in new waters and getting something out of my system but I didn’t consider that in going off-brand I would make it harder for my publishers to sell. The lesson I took was to go back to what I know and love – and do – best. But first I took a little detour to Dorset.

Book Five: Broadchurch

A weird little privilege, this project. Only a handful of novelists have adapted a TV drama for the page. This book is a bit like Paul McGann playing Dr Who. There will always be some people who don’t believe it counts. Broadchurch is not my work, and yet it is. I loved writing this book, and not only for the lazy reason that the heavy lifting of the plot and the characterisation was done for me, and done to perfection.

My job as a novelist was to read the characters’ minds and set their thoughts on the page. Finding the right words is my favourite part of writing. Watching Olivia Colman, David Tennant, Jodie Whittaker act was like taking dictation. Broadchurch was a masterclass in character. The arc of Series 1, while compelling, is more linear than my own storytelling style; the magic is in the people and the place as well as the plot. My brief was to write up: find language that did the stunning photography and performances justice. I’m proud of the result, not least because I made showrunner Chris Chibnall cry, which was only fair after he’d done the same to millions of viewers.

Book Six: He Said/She Said

This, my current book, feels like a debut in some ways. Since The Ties That Bind was published, Broadchurch, and a second child, and a teaching job had happened so He Said/She Said had the luxury of a long gestation period. I was in the mood, and had the energy, for something big and ambitious.

For the first time research could not be taken lightly. The plot of He Said/She Said turns on two very different technicalities. Firstly, it happens over the course of several total solar eclipses, and I loved learning about the phenomenon and the people who travel the world to witness it.

More importantly, it’s courtroom drama about a rape trial, and points of law cannot be fudged. The challenge here was to highlight the mechanics and the frustrations of our justice system in a way that served the story. Laura is the prosecution’s star witness: when I realised she wouldn’t be allowed to see the victim’s testimony in case it prejudiced her own, I had my head in my hands. How could I write a serious novel about the horrors of victim cross-examination if we couldn’t get into the courtroom? In the end I had to take my own advice. I often tell my students that the problem is the solution. When we can’t see the victim, Laura’s own doubt is allowed to spiral, and along with it the reader’s. That lack became a driving force.

In other ways, He Said/She Said was back to basics. Broadchurch had reminded me of the importance of character. I re-read old favourites by Chris Cleave, Lesley Glaister, David Nicholls, Maggie O’Farrell and new favourites Susie Steiner and Sarah Stovell where to close the book feels like saying goodbye to a friend. I loved Kit and Laura. I don’t know why I put them through all that.

I also feel a hard-won sense of ownership and authorship with this book. I’ve said before that Barbara Vine, Daphne du Maurier, Patricia Highsmith hugely inspired my work and they still do, but I don’t consciously measure myself against them like I did in the beginning. Anxiety of influence has been something I have gradually shrugged off over six books. This, at last, is all mine.

Book Seven

Is it tempting fate to include here a book that isn’t finished yet? The deadline for my seventh novel was last week. Present ambitions are to complete it this decade.

It’s set in a former Victorian asylum, the action starting in the present day and leaping backwards over sixty years. The structure of the novel – three acts, each set thirty years apart – was part of the idea. It begins when a Woman With A Past enters what is now a luxury apartment carved from the old women’s wing. The first few chapters flew out of me, mystery and menace on every page, building to an impossible climax. Then I had to find a way to maintain that suspense writing scenes from 1988 and 1958 without sacrificing momentum. Clearly my experience with The Burning Air has taught me nothing.

For the last ten months, I’ve been camped out in the Wellcome Library in London researching the way psychiatry has historically treated women. Spoiler: the system hasn’t been stacked in their favour. The problem for me is focus. Every long-dead case study in these dry textbooks is a novel waiting to be written. Consequently, I feel like I’m writing a Choose Your Own Adventure book. Every time I learn something new, I find myself writing another doomed scene that is more about me showcasing my new knowledge of outdated psychiatric processes than it is about furthering the plot.

Or is it? I said I’d learned nothing from The Burning Air but that’s not true. I feel patience rather than panic this time. I’m trusting myself, and the process. One of these scenes will be the right one. It feels close, now. I won’t finish it when I had hoped to, but abandoning it doesn’t cross my mind.

And when I do complete it? Book eight, and beyond, with all the excitement and challenges they will bring. I know that it doesn’t get easier, but I also know that I – and my readers – would be bored if it did.

Read the first few chapters of He Said/She Said here